SAFE WATER AND AIDS PROJECT (SWAP)

A network of trained community health promoters, primarily drawn from vulnerable community groups, who earn an income conducting door-to-door sales and provide education to improve health and increase access to health and hygiene products for their communities.

CONTINENT

Africa

Country

Kenya

Organizational structure

Nongovernmental organization

Health focus

Primary health care, HIV

Areas of interest

Community health workers, Community mobilization

Health system focus

Health workforce

CHALLENGE

Kenya has a high prevalence of communicable diseases, which places a major burden on the health system as well as the economy at large. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the leading cause of mortality in the country, at 14.8% (World Health Organization, 2015a). There is a high prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) infection, as well as a co-infection rate of 45% for TB and HIV (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics & ICF Macro, 2010). Poor health is exacerbated by poor water quality and inadequate sanitation. Diarrhoeal disease remains one of the major causes of childhood morbidity and mortality in Kenya, particularly in areas where there are shortages of safe drinking water (World Health Organization, 2009). Correctly used public health products (e.g. bed nets, household water treatment, hygiene products) have the potential to be a cost-effective way to improve the overall health and productivity of communities.

“I think what makes our work innovative is the combination of health and economic improvement, which really complement each other. It makes an income for the women who are vulnerable: women living with HIV, widows… They become self-reliant while they also adopt healthy practices themselves. It has reduced stigma and discrimination for people living with HIV, who have become useful members of society.”

– Alie Eleveld, Founder, SWAP

INTERVENTION

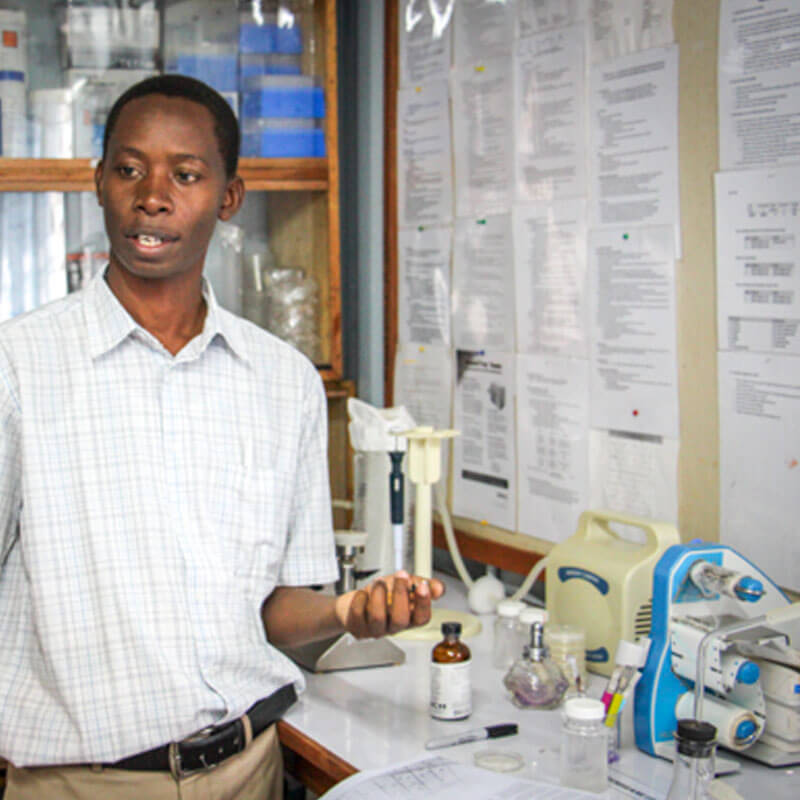

The Safe Water and AIDS Project (SWAP) is a community health network that utilizes best practices from public health, business and research. It prioritizes economic and social empowerment for marginalized community members and resource-poor communities in rural Western Kenya. SWAP identifies, recruits and trains community health promoters (CHPs), whose role is to go door-to-door in their local communities, educating households and promoting good health practices. In addition, CHPs are able to generate their own income through the sale of health products and become economically self-sustaining. CHPs are recruited and trained at no cost to themselves and are then given products on credit at wholesale prices to sell in their communities at retail. A CHP can earn a profit of up to US$ 110 per month, depending on the number of households visited.

SWAP sets up Jamii (meaning ‘community’) Centres, which operate as central business hubs for the CHPs of a given area. These Jamii Centres are usually set up at the local government health facility and are run by a SWAP project officer. CHPs visits the Jamii Centre on a weekly basis to reconcile stock and data, take their profits and get new stock. The project officer at the Jamii Centre provides ongoing mentoring and training to the CHPs. Additional training is provided in targeted subjects by external partners. In 2007, SWAP established its research department, which conducts studies on the impact and effectiveness of products and methods, and provides an avenue of revenue generation.

“For me, [SWAP] is a body that changes lives. In areas where we have worked, people have given testimonies that, ‘before I was not treating water, I had these diarrhoeal cases here and there. But since I started working with SWAP, it’s changed my behaviour from not having safe water to now consuming water which is safe.’ And for CHPs, their living standards have also changed.”

– SWAP Jamii Centre Project Officer)

In 2014, 45 different health products were distributed by the trained community health promoters, including 25 411 bottles of Waterguard (chlorine solution), 73 630 mosquito nets, 111 083 sanitary pads and 236 516 bottles of detergent. In addition to the income-generating benefits of the model, the impact of improved access to health-related products and education on the local communities is identified in a number of multi-year studies. A survey done in 2014 in SWAP’s intervention area showed mosquito net use up to 93%, hand washing up to 59%, with soap and clean drinking water treatment up to 54% in the targeted households around the Jamii Centres.

CASE INSIGHTS

The LMH case study illustrates how nongovernmental organizations can play a unique role in health systems strengthening by absorbing the experimentation risk for new innovative service delivery models, providing the financial backing and creating data systems to assess impact. It shows how country governments in turn can promote the adoption and scale of effective models. CHW programmes have significant potential to improve health care delivery to people living in rural and hard to reach areas if the programme incorporates best-practices at each stage including recruitment and selection; training; equipment and supplies; and performance management.

“They do door-to-door sales and health promotion. So they will check in the home: Is the pregnant mother going to the clinic? Are the children immunized? Is there safe water in the home? Do they practise hand-washing? Do they sleep under a mosquito net? And all these other primary health issues. A lot of them are really vulnerable women – that is widows, people living with HIV from very poor backgrounds – who are now economically empowered. So they make an income while they improve health.”

– Alie Eleveld, Founder, SWAP