Capacity strengthening for social innovation

CAPACITY STRENGTHENING

FOR SOCIAL INNOVATION

By Rosanna Peeling

From 2 to 3 November, 16 participants from different backgrounds came together in Cape Town to explore the various mechanisms of capacity strengthening that could be applied to social innovation in health.

The consultation started with each participant having a different definition of social innovation and different levels of understanding as to who the actors are and what type of innovation is possible. At the end of the two-day consultation, however, we were all on the same page. We left with a shared vision of how social innovation can enhance healthcare delivery worldwide.

We reached consensus on a set of guiding principles to achieve social innovation and importantly, a research framework for TDR to monitor whether the social innovation is achieving its goals. If not, how risks can be identified and mitigated before the innovation fails.

I used to think social innovation is just about people with novel ideas that are put into action for a social good. After listening to the two social innovators at the consultation, I started to think more deeply about the importance of research methods in understanding the inequity that needs to be overcome to continously improve or scale up an innovation. For example, one of the innovators did a randomised controlled trial to decide on the best option. Impressive!

The most important message that arose from the meeting, is that we should not think all the solutions for healthcare delivery should come from the north. Communities in the Global South have much wisdom that should be recognised and celebrated. We need to learn from each other.

Social innovators are people from diverse backgrounds, working at grassroots level. They are normally not researchers. The Social Innovation in Health Initiative plays an important role in recognising excellence, disseminating out-of-the-box models for improving healthcare delivery, and organising workshops to allow innovators to share their experiences and learn how to use research to improve their innovation.

IDEAS THAT CHANGE LIVES

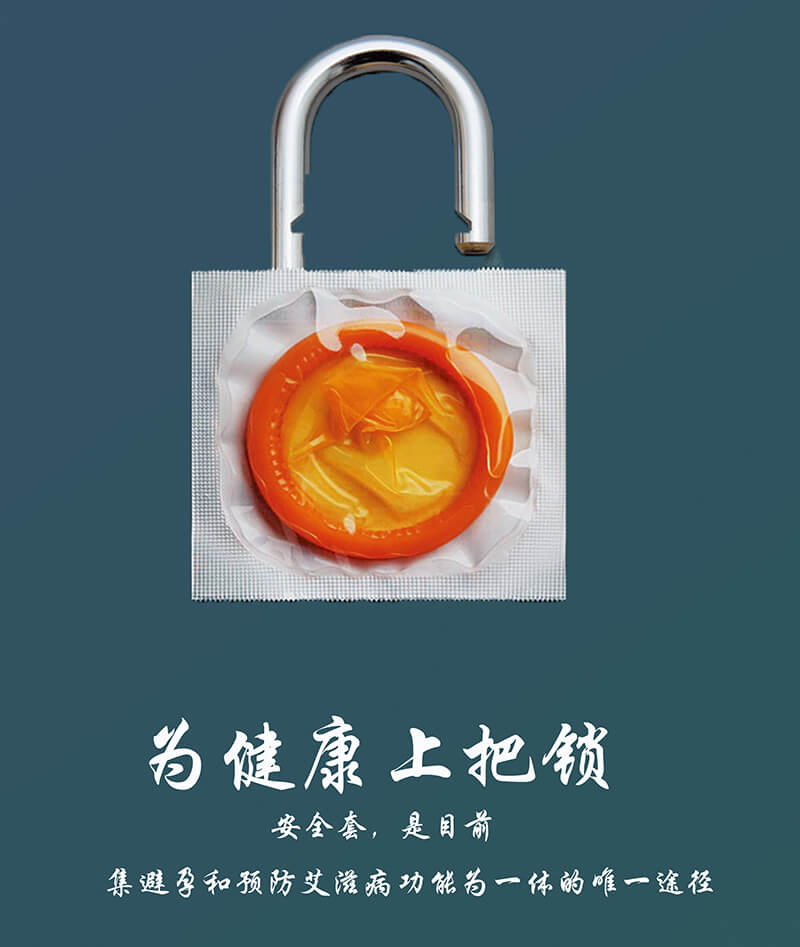

SOCIAL ENTREPRE-NEURSHIP FOR SEXUAL HEALTH (SESH)

Q&A

WHERE ARE YOU BASED?

China

WHAT PROBLEM/S DO YOU ADDRESS?

HIV testing rates in China are low and sexual health messaging tends to be old fashioned and unengaging. Delays in HIV testing directly contribute to severe opportunistic infections and the related consequences of late-stage diagnosis. It also leads to persistent high-risk sexual behaviours and opportunities for ongoing HIV transmission. Creative ideas from diverse sources are urgently needed to recast HIV and expand its testing. The generic messages that have been developed by experts must be replaced by tailored, locally appropriate messages using diverse, creative inputs.

WHAT IS YOUR INNOVATIVE SOLUTION?

SESH is a multi-sectoral research collaboration that utilises creative contributory contests to crowdsource sexual health messaging. These messages are directly informed by the lives and experiences of the target population. We take a ‘bottom-up’ approach that taps into the wisdom of crowds to generate appropriate and engaging materials. It allows for greater inclusion of perspectives from diverse community members. It also possesses higher potential for innovation, compared to conventional expert-led approaches.

HOW CAN YOUR SOLUTION BE IMPLEMENTED IN OTHER COUNTRIES?

The participatory open contests are highly scalable and can be implemented in a wide range of geographical and socio-economic contexts. Our bootstrapping model of tackling health problems works across resource-constrained contexts, because of the following attributes: 1) low cost – participatory open contests are inexpensive; 2) focus on community engagement – tapping into the local wisdom of communities makes contests more likely to be community responsive; 3) sustainability – contests could improve products sold as part of a social enterprise in order to stimulate revenue generation.

These open contests could be an effective tool for generating new concepts to optimise community-based infectious disease control, developing health communications strategies to change behaviours and prevent infection and developing mobile phone applications to strengthen retention in infectious diseases care.

LEARNER TREATMENT KIT (LTK)

Q&A

IMPLEMENTERS

Save the Children Malawi, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, College of Medicine, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

WHERE ARE YOU BASED?

Malawi

WHAT PROBLEM/S DO YOU ADDRESS?

Malaria is a major contributor to school absenteeism with schoolchildren being most commonly infected, but least likely to have access to treatment. In Malawi, children are estimated to experience 2.1 million clinical attacks of malaria annually. Within school-aged learners, 60% of children are infected with Plasmodium Falciparum. Most malaria cases in the age group 5 to 14 years are never treated due to lack of access to health facilities.

WHAT IS YOUR INNOVATIVE SOLUTION?

We sought to address the issue of undiagnosed and untreated malaria in schoolchildren by mobilising our communities. By training teachers in 58 schools in the Zomba region, they have been empowered to perform malaria diagnosis and treatment for learners right in the schools. Along with the training, each school receives a ‘first aid box’ – filled with common supplies required by children who fall ill at school, as well as malaria rapid diagnostic tests and antimalarial medicines.

HOW HAS YOUR SOLUTION IMPROVED HEALTHCARE?

Preliminary monitoring data show that use of the LTKs and malaria treatment far exceeds expectations. In January and February 2014 alone, 6 363 malaria tests were performed by teachers and 4 962 of these were positive and subsequently treated. Anecdotal evidence has reported a reduction in absenteeism from school, but the results of a randomised control trial will be known in 2016.

FROM OUR PARTNERS

CATALYSING INCLUSIVE INNOVATION FROM THE INSIDE OUT

By Dr Lindi van Niekerk

Not long ago, I found myself as a newly qualified doctor in the public health system of South Africa. Despite entering it with enthusiasm to change lives, reality soon hit me.

Faced with the daily challenges of providing patients with just the basic care, sometimes without resources to treat them, rocked me to the core. At this stage, I was still young and encouraged. I had an idea. After months of pondering, doing background reading every night, coming up with proposals and plans, I braced myself to share my idea with colleagues. One day I piped up: “I think I have an idea about how we can make things better for this specific patient group.”

The response was completely overwhelming. Laughter erupted and my senior consultant replied: “My dear, don’t ever think you can do something like this. You’re just a junior doctor. There’s no money in the public services and even if there was, these ideas never last.”

Despite their reaction (and a few tears later), stubborn persistence prevailed and I received seed capital from a volunteer organisation in Cape Town. I secured support and mentorship. Today, many years later, that very idea is still being implemented in the hospital. It has also spread to other hospitals in the city and continues to improve care for patients.

We always complain about the faults and challenges within the healthcare system. It is our favourite thing to blame. Despite our knowledge of the ‘failing’ system, we often miss opportunities that lie within it to bring about change and improvement in healthcare.

But who is the system? Although we refer to it in third person, the system is all of us. Every single person who enters the health services daily with a very specific task: to deliver care to a patient. It is everyone from the nurse to the cleaner to the senior consultant, administrative clerk or head of the hospital.

The reality I experienced within the health system is the same reality my colleagues at the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship have experienced over the years. United by this idea of changing health services through ideas, we started a body of work at the Bertha Centre. It focused particularly on healthcare innovation and innovation in healthcare delivery.

The Bertha Centre is the only academic centre in Africa that focuses on social innovation. We span from an academic centre to one very engaged in the practical implementation of programmes. We try and apply the lens of social innovation to some of the pressing issues. To learn, to understand and to see what effects we could have on healthcare delivery. For many of us, it has been a personal journey, leveraging the experiences that we have had.

We ask ourselves: what is the role we play? We are not the innovators, despite our previous experiences. Instead, we see ourselves as the enablers or catalysts of innovation in our local healthcare system. It’s our role to find, support and nurture innovators and their innovations.

One of our core beliefs at the Bertha Centre is that we cannot change healthcare by sitting on the outskirts. Change can only take place once we have embedded ourselves deeply within the system.

In July 2014, we were fortunate to partner with Grootte Schuur Hospital. It is one of the oldest and biggest hospitals in Cape Town. In 1967, the first heart transplant was conducted at Grootte Schuur. So there exists a legacy of innovation, yet over the past few years it has been sidelined in terms of service delivery.

We got the opportunity to design a programme. So, we spent time engaging with people throughout the hospital – about their challenges and issues they face to deliver healthcare every day. We looked for similarities. Within a few weeks, we identified key challenge areas that were really amenable to innovation. We discovered that everyone faced similar challenges – from the porter to the senior neurologist. Staff members had the opportunity to share their ideas. For many of them, this was a novel request. They had never been asked for their ideas.

It took some courage and several weeks for people to start sharing their ideas. We uncovered so many existing solutions and new ones that could be developed. In February 2015, we launched the innovation programme. We selected ten teams, each with a brilliant idea. They received seed capital, as well as technical expertise and mentorship to take their pie in the sky idea and turn it into reality.

Some of these simple solutions have been implemented and are already having an impact on patient care. These interventions range from a new clinic for adolescent patients with kidney failure to a coaching initiative to support the nursing staff within the surgical ward.

The main value of this capacity building programme does not just lie in the solutions that have been developed. The real value goes much deeper. Some of the findings point to deep internalised change that took place for many of the front line staff who have been engaged with the programme.

You realise how this experience has changed their perceptions of themselves. For instance, a nurse had this to say: “I always thought innovation was for creative people, like designers, artists and architects. Not for me. But I learned that I can be creative in finding solutions in my profession.” A junior doctor shared this: “It helped me to see a bigger picture. Not just myself as a medical doctor, but that I can do something bigger than just being in a consultation room. If you think about the system, there are so many ways you can improve it. It opened my mind. Her reflections reminded me of my own journey.

So is innovation possible in public services? Definitely. Does it lead to improved interventions? We are seeing the proof in Cape Town. Could it lead to system-changing effects? The verdict is still out. But we believe that through changing the beliefs, the way people see themselves, their management team and role in the system, can have lasting effects that could lead to change that continues to happen.

Through our work at the Bertha Centre, we hope to transform the depths of the people within the healthcare system. From these changes, innovation will really flow from the inside out.

FROM THE COMMUNITY

LESSONS FROM THE KENYAN HEALTHCARE LANDSCAPE

This report from the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship explores how policymakers can take advantage of the lessons learned from Kenya’s healthcare sector.

OUR PARTNERS