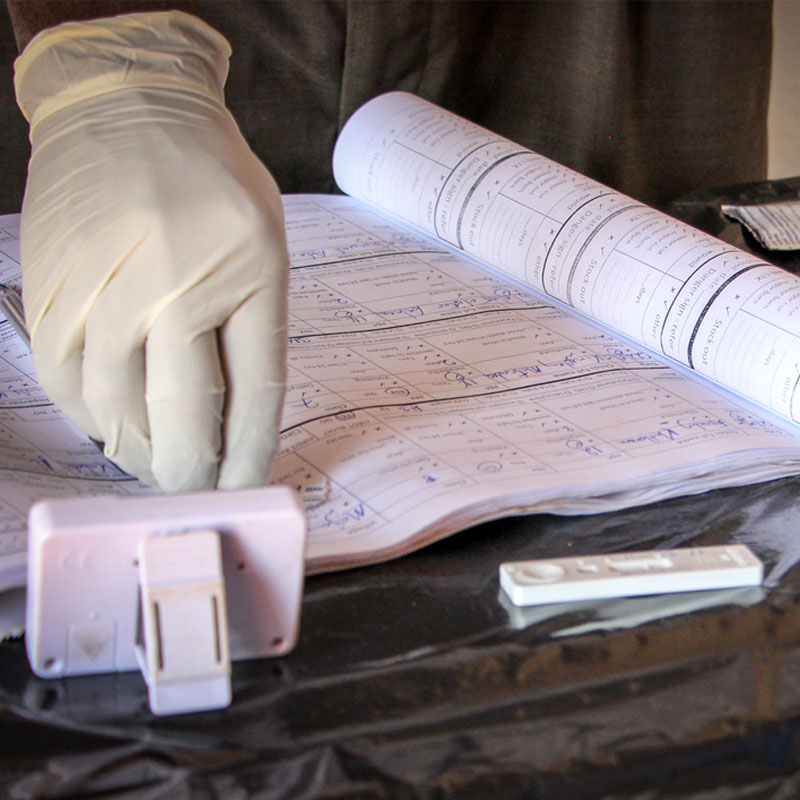

LEARNER TREATMENT KIT

CONTINENT

Africa

COUNTRY

Malawi

Continent

Africa

Country

Malawi

Implementers

Save the Children Malawi; Ministry of Health; Ministry of Education; College of Medicine, University of Malawi; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK

Founding year

2011

Organizational structure

Nongovernmental organization (Save the Children)

Health focus

Malaria

Areas of interest

Digital technology

Health System Focus

Information systems

CHALLENGE

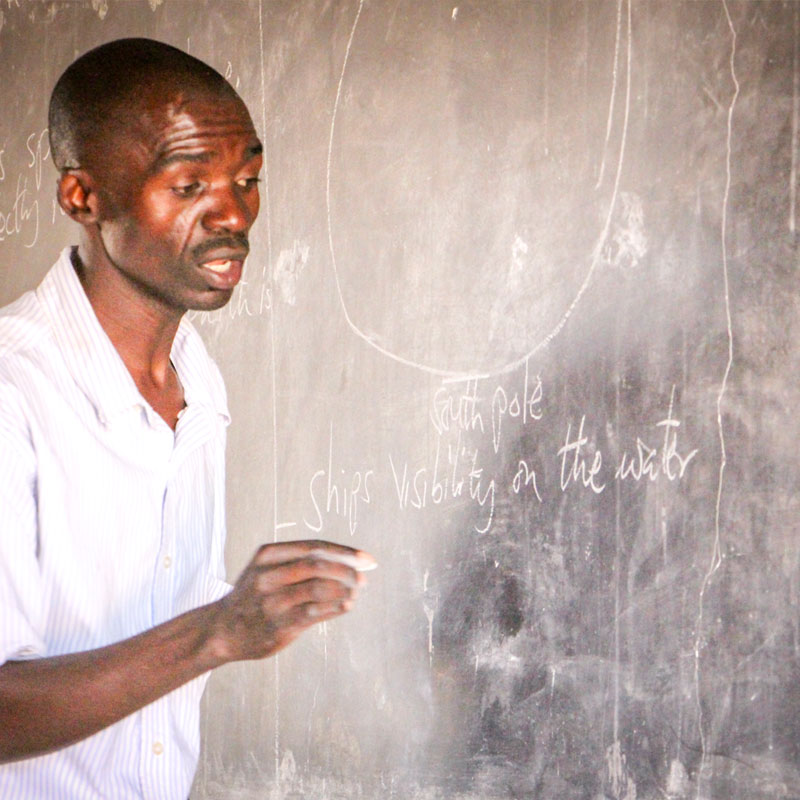

“Because if learners are treated within the school, there is a smile on the face of the parents. Because it reduces the burden of travelling long distances to go to health services. They concentrate on their day-to-day activities. Productivity at the household improves because they are not spending time admitting the child to hospital etc. There are a lot of economic benefits from this mere simple intervention.”

– National Education Officer, Lilongwe

INTERVENTION

“So we are proud of [this initiative]. We are contributing something to the entire world to learn something from what we have done using whatever we may have. We might not have everything. But using what is available, we have been able to achieve this.”

– National Education Officer, Lilongwe

Of tests performed, 75% of children (n=16 322) were positive for malaria and were able to receive immediate treatment. A preliminary cost-effectiveness analysis comparing the initiative costs to health facility costs showed it to be a cost effective intervention, even with changing assumptions (Sande, 2015).

CASE INSIGHTS

“My dream is to see various players, stakeholder and communities both professional, laypeople and other disciplines that may not be necessarily be professional health workers, participating. There is a lot that the community can do in our health care … So when we trust each other, when we work together, we can build a health system that we can deliver to the people.”

– Austin Mtali, Save the Children